It 's easy to understand why the people of Baptiste Lake might feel negatively towards the stinky, scummy, potentially toxic layer of film that graces their resident body of water and its shores every year.

Alberta Health Services recently maintained its mid-July advisory, urging those living on the lake to not drink its water, eat its fish or come into contact with the blue-green film that has formed on the lake's surface and shores.

But looking deeper, we owe a lot more to this scum-like nuisance than we give it credit for.

The fact is, blue-green algae is not algae at all, nor is it always blue or green.

The scum that graces Baptiste Lake every year is actually massive colonies, or blooms, of cyanobacteria, says Dr. Sue Watson, an Environment Canada scientist at the Canada Centre for Inland Waters in Burlington, Ontario.

"It 's a very important distinction to make, " she says. "Because they 're bacteria it gives them certain properties that other organisms don 't have. "

As a class of bacteria, they tend to grow and spread very quickly, and they 're very opportunistic.

"Cyanobacteria are found in every single environment, if you look hard enough, " she says, adding that they range in colour from blue, to red, to black, to yellow.

It 's our waste, rich in the food these bacteria love to chow down on, that is fuelling blooms in five lakes in Alberta, and countless others across the country.

As agriculture and residential development rolls on, nutrients like phosphorous and nitrogen seep through the soil and enter bodies of water like Baptiste Lake.

These nutrient-rich ecosystems are the perfect incubators for cyanobacteria.

As they find their niche, sucking up abundant nutrients, they divide and grow exponentially like any good bacteria. That 's when they start causing problem for humans.

In their efforts to produce energy, some species of cyanobacteria release noxious chemicals into the surrounding environment.

Those toxins fall into three categories, each affecting a different mammalian system.

There 's the hepatotoxins, known as microcystins, that if ingested or inhaled will rapidly poison the liver, and can lead to death. Long-term, low-level microcystin exposure is a known carcinogen.

Then comes the neurotoxins, a fast-acting poison taking aim at the nervous system, causing paralysis and eventual death from suffocation.

"That is a major problem in the prairie provinces, " Watson says.

Although no human deaths have been reported, animals with less discerning tastes, like dogs and cattle, have died from drinking tainted water, with the first outbreak in the early 1800s.

And finally, the least dangerous of the trio, dermotoxins, irritate or inflame mucuous membranes, including the inner ear, throat and nose.

The toxin-producing species have given the rest a bad name, she says, adding that many are harmless, even beneficial in moderate amounts.

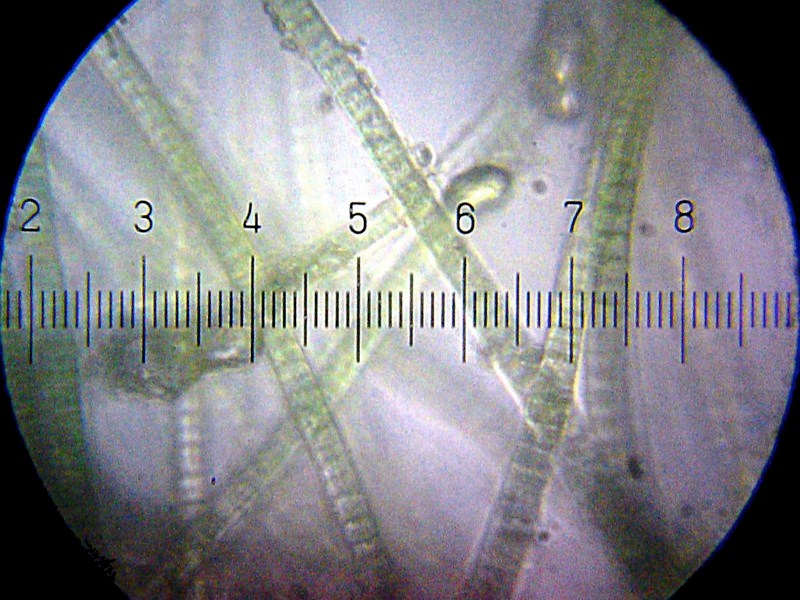

"Under a microscope you can identify their species, " she says. "However, the problem is that within that particular group or species, there 's some that produce toxins and some that don 't. "

That difficulty is compounded by the fact that many blooms will be made up of two or more species, which can then only be determined by lab tests.

That 's why it 's best to err on the side of caution, she says, an idea reiterated by Dr. Kathryn Koliaska, medical officer for Alberta Health North.

"The whole point of these advisories is to make it so people can 't even remotely get close to these symptoms, " Koliaska says, adding that toxin levels will continue to be monitored until it 's safe for swimmers to return to the water.

But it 's not like the people around the lake aren 't used to being kept at bay.

One resident who has spent almost every summer of her life on the lake said she has never let it affect how she enjoys the area, since the toxic blooms only last for a few weeks.

Looking back a bit further, we find these instances constant throughout our history, with the earliest recorded blue-green bloom happening in the 12th century.

But we must dig deeper, literally, to find out how cyanobacteria really impacted the human species, in ways far greater than stopping us from jet skiing at our summer retreat.

"Very simply, they 're survivors, " says Murray Gingras, a professor of geology at the University of Alberta.

In his work, Gingras has dug into the depths of the earth, studying the relationship between animals and sediment, a field known as geobiology.

His studies have made him particularly knowledgeable about cyanobacteria 's role in Earth 's history.

"They 're the first fossil form of life on the planet, they go back at the very least to 3.5 billion years ago, " he says.

To put that into perspective, the Earth is estimated to be around 4.5 billion years old.

Back in those days our world was a much different place. The atmosphere, a toxic concoction of methane, ammonia and other gases would have humans keeling over in seconds.

It was in the oceanic primordial soup that cyanobacteria evolved.

They began by using atmospheric nitrogen for energy, and eventually, around three billion years ago, developed the first known photosynthetic mechanism, gaining energy from sunlight. Scientists theorized that at some point, cyanobacteria entered into symbiotic relationships with larger cells, the early ancestors of present-day plant life.

"Cyanobacteria were important for preparing the world as we know it, " Gingras says. "It 's almost certain that they were the most important player in what we call the great oxygenation event. "

Now this great oxygenation event sounds like a party, but it was actually the snail-slow process of converting the nasty atmosphere into something a little more hospitable.

Getting into the groove about 2.4 billion years ago, ocean-dwelling cyanobacteria continuously pumped out atmospheric oxygen for the next 1.9 billion years. In the end, the bacteria had puffed up our world 's atmosphere to 15 percent oxygen, up from a gasp-worthy one percent from when they started.

Now this is the sad part. Many a cyanobacteria and other microorganisms died because of the corrosive nature of oxygen, one of the first mass extinctions of the Earth 's history.

To top it off, the oxygen-rich environment they created just happened to be perfect for the evolution of early animals, like worms.

"When animals evolved cyanobacteria became food, really for the first time, " Gingras explains.

When they once covered the sea floor in great jello-like mats, cyanobacteria began to lose the evolutionary battle by the Cambrian era, about 500 million years ago.

"This is when cyanobacteria started getting pushed into the more marginal niches, " he says. "They are most successful in areas where animals and other organisms really can 't have success, and that continues on to today. "

That 's why they bloom annually in lakes across the country today.

"We put lakes on the edge of healthiness, and they become more and more like the Precambrian world, " he says. "Predominantly people have to look at themselves, not the cyanobacteria. "

Luckily enough, scientists like Sue Watson are doing just that, hoping to mitigate the impact this ancient life form has on our own species, and vice versa. Her work has focused on bacterial and algal blooms that affect drinking and recreational water across the country.

"What really needs to be done is large-scale, long-term reduction of nutrient input, " she explains, emphasizing that although people are quick to blame farmers and industry, human sewage can have just as great an impact, since it 's high in cyanobacteria 's most crucial nutrient, phosphorous.

Even though there are short-term solutions, like an aerating machine that swims around small lakes preventing cyanobacteria from gaining a foothold, it's that long-term solution that will make the difference.

Soon enough, residents at affected lakes will be able to return to their waters, counting down the days until next year's bloom.

For now, they may be well off to thank that stinky, scummy layer of film floating at the surface.

Because without cyanobacteria, none of this would be possible.