ATHABASCA — Wastewater, the new scientific frontier for tracking disease.

In a presentation for Science Outreach – Athabasca Jan. 11, Dr. María Bautista, a research associate at the University of Calgary and a member of a team studying wastewater surveillance for COVID and other viruses, explained how science is evolving in response to the pandemic.

“The pandemic kind of happened and kind of changed the entire face of this field,” she said.

Wastewater surveillance (WWS) isn’t new to science but using it to track a pandemic is, and it is how on the nightly news reporters can refer to outbreaks on the east side of Calgary or in downtown Edmonton.

“We can use this wastewater surveillance to detect viruses that are circulating within the community,” said Bautista. “We can monitor all sorts of things and within a population using this pooled wastewater, we can track infectious disease, the spread of resistance to antibiotics, pharmaceuticals, the emergence of new diseases, but also outbreaks of old diseases that we know, and we think we have in hand, and we actually don't, and we can do it in real time. And at a relatively low cost, which is so important.”

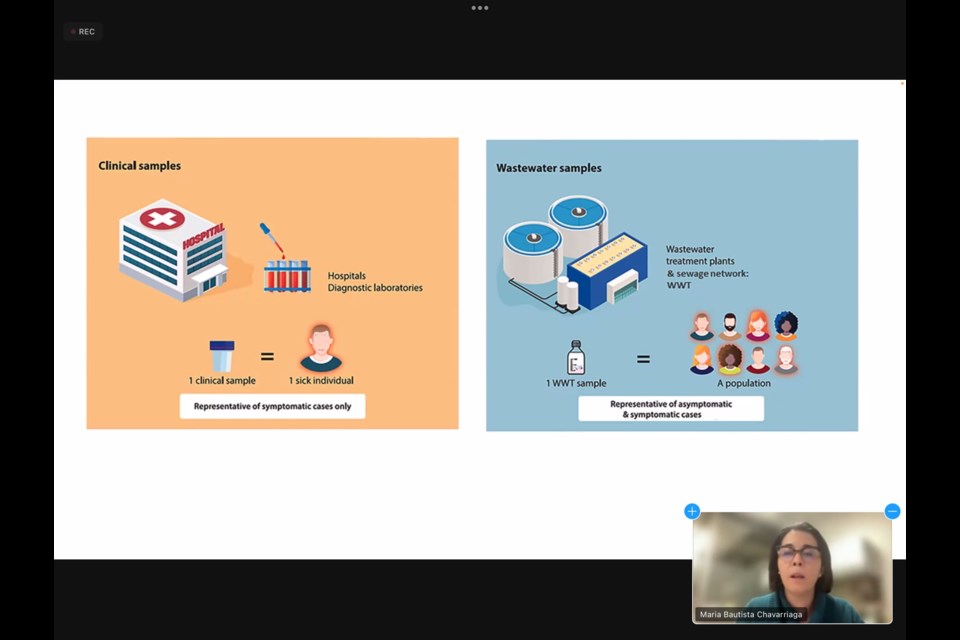

Two years ago, everyone used the words symptomatic and asymptomatic but what did that mean? Symptomatic people were obviously sick with the virus, but asymptomatic people were carriers – infectious but otherwise appeared healthy, which made it hard to track the disease in a normal clinical setting.

“Because you don't have any symptoms, but you're also sick, those numbers usually get lost or don't get really measured, because a person that is asymptomatic wouldn't necessarily go get tested,” she said. “And so, it is unbiased in that way that everybody contributing to that sewer system is included in that sample.”

While researchers can’t trace it back to a particular residence, they can narrow down the area because samples can only be taken from certain locations. No one is cracking open a sewer pipe and hanging out with the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles collecting samples.

“Wastewater treatment plants can service thousands, tens of thousands, or hundreds of thousands of people,” said Bautista. "Once you flush the toilet, that's it, that sample is there, and it's anonymous. So, if for some reason you didn't want to get tested … this is a way that the result will be part of the pool.”

When scientists were scrambling to contain polio in the 1940s, they collected waste samples, concentrated it, and injected it into monkeys to see if they would develop polio.

“Please keep in mind that the ethical regulations at the time were very different,” she said. “These are experiments that today, of course, would not be something that could be done or approved.”

But it was the early steps into the field which really developed in Israel starting in 1989.

“The first sewage surveillance system was actually started in Israel. It was started in 1989 because they've had an outbreak ... in 1988,” said Bautista. “So, they decided to start a program (and) just monitor … the sewage (and) nothing happened for a long time; from 1989 to 2013.”

In 2013, polio was detected and it was traced back to a Bedouin community that had arrived though Syria where it had spread to several countries.

“Thanks to this warning system, the Ministry of Health worked quickly, they vaccinated the public, and none of the infections resulted in paralysis,” she said. “So, it was really kind of worth having set up that system, even if you had run it for decades, and nothing had popped up.”

Using WWS the Netherlands was able to detect SARS COVID-2 RNA in the sewage six days before the first cases were reported.

“You can be making other people sick, and yet you can feel totally fine, and a couple of days will pass and then you'll feel sick,” said Bautista. “So, this was detected in the wastewater and the sewage. People could detect the signal before any clinical cases were actually reported.”

The nucleic acids, which encompass both DNA and RNA, are the fingerprints of each living and non-living biological entity on the planet, she said.

“(Viruses) have nucleic acids as their blueprint, all of their information is there, and so scientists can design specific probes for each of them,” said Bautista. “So, you can distinguish all of them from each other, you can distinguish variants.”

When scientists know what they are looking for they put in a “probe” which will only bind to and produce fluorescence (light) if the target is there.

“If our target is not there it's not going to bind because it's very specific," she said. “And because it's also quantitative, and it's linked to fluorescence, the more fluorescence you see, the more virus ... is in the sample.”

But COVID-19 isn’t spread though the fecal-oral route so how does it end up in the sewers?

“If you think, and it's kind of gross, what happens when you're sick? You're swallowing snot all the time so, you're kind of eating the virus, and it makes it through and then makes it out,” she said.

If you want to avoid being sick, regular, proper handwashing is key.