ATHABASCA/BARRHEAD/WESTLOCK - What’s better than a strong cup of coffee on a Monday morning to start your week? Perhaps a giant, speeding fireball from the edge of the solar system lighting up the pre-dawn sky across two provinces?

It was a spectacle to behold the morning of Feb. 22, as thousands across Alberta and Saskatchewan witnessed the large, blue, mass of extraterrestrial material burn up in the Earth’s atmosphere and turn night into day for a few seconds at approximately 6:23 a.m. Thousands of others reviewed the relatively rare celestial event in their security footage afterwards, and shared it across the world.

These are the kinds of things that pique the interest of people like Athabasca University’s Dr. Martin Connors. The long-time AU professor has been watching the skies for years as part of the Faculty of Science and Technology, with the help of some very specialized equipment. While a lot of the research he is now conducting deals with the aurora borealis; the university’s geospatial observatory also caught a glimpse of what has now been classified as a small piece of a comet that burned up in the atmosphere.

And it was almost completely by mistake.

“We normally would not be picking up meteors like this anymore,” Connors said in an interview Feb. 25. “The reason we got this one was that we were testing some aurora equipment. Normally our equipment turns off at dawn and our normal aurora equipment already had turned off, but the test equipment hadn't turned off yet.”

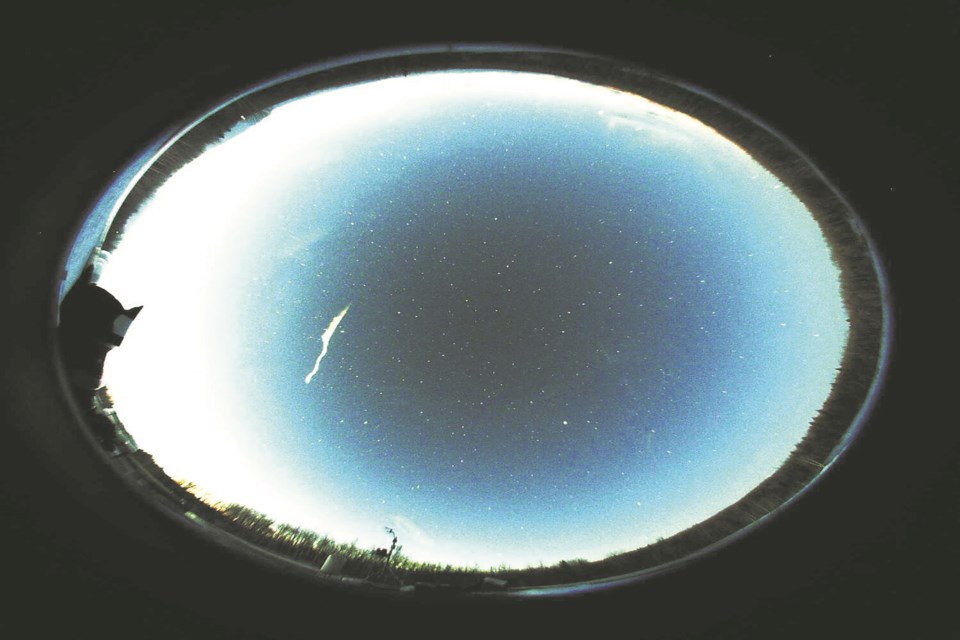

The AU imaging equipment is very light sensitive as it is designed to measure faint aurora, and not necessarily incoming space rocks, so the tail of the comet is the most visible feature in AU’s images.

Your normal meteor camera is meant for bright objects. So, we were completely blinded by it. That is to say, during the actual explosion, our images are pure white, there is no information there, the whole place lit up,” said Connors. “Our cameras are meant to detect very faint auroras, and so they were blinded by that, but the flip side is after it subsided, we could track the dust trail for 10 minutes, and it becomes what you might have seen on TV. It all goes by rather quickly, but there's a little curlicue afterwards.”

The University of Alberta does have equipment designed to capture these events when they occur, due to an Australian technology that allows the object to be coded, then read by researchers to learn the time, trajectory, speed and where it came to rest.

In this instance, there was speculation the remains of the fireball landed near Athabasca, but it was found this was likely a very small piece of debris made up of dust and ice that disintegrated at 46 km above the ground, making it visible across Alberta and Saskatchewan, said U of A researchers.

“Using two observation sites, we were able to calculate both its trajectory and velocity, which tell us about the origin of the meteor and reveal that it was a piece of a comet,” said Patrick Hill, post-doctoral fellow in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at U of A, in a media release Thursday. “This chunk was largely made of dust and ice, burning up immediately without leaving anything to find on the ground — but instead giving us a spectacular flash.”

They also found it was travelling at 220,000 kilometres per hour.

“This incredible speed and the orbit of the fireball tell us that the object came at us from way out at the edge of the solar system — telling us it was a comet, rather than a relatively slower rock coming from the asteroid belt,” said Chris Herd, curator of the UAlberta Meteorite Collection and professor in the Faculty of Science, in the same media release.

“Comets are made up of dust and ice and are weaker than rocky objects, and hitting our atmosphere would have been like hitting a brick wall for something travelling at this speed.”

The U of A team calculated the trajectory of the fireball using dark-sky images captured at the Hesje Observatory at the Augustana Miquelon Lake Research Station and at Lakeland College’s observation station in Vermilion.

“This is an incredible mystery to have solved,” said Herd. “We’re thrilled that we caught it on two of our cameras, which could give everyone who saw this amazing fireball a solution.”