Dr. Eva Olsson knows first hand about the power of hate. She also knows about how compassion, when acted upon, can combat the darkness of hate.

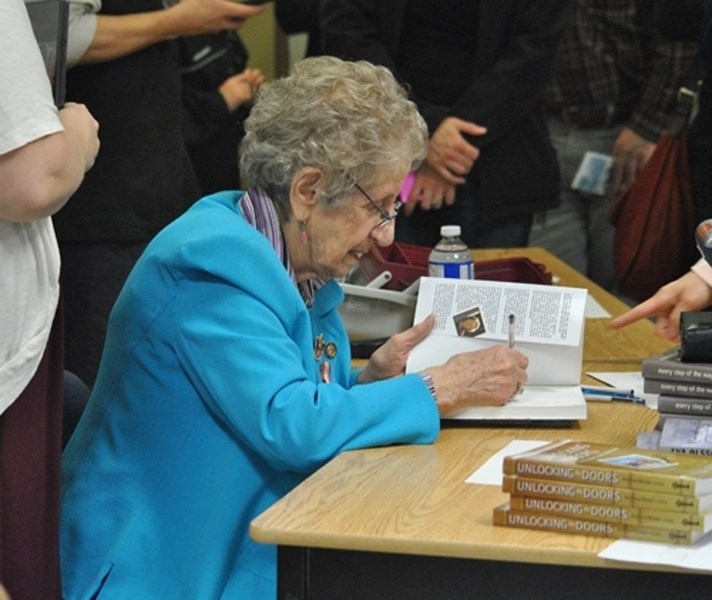

That is the message, Olsson, a 90 year-old Holocaust survivor, is bringing to audiences everywhere she goes during her latest western province tour, including a stop in Barrhead on Monday, April. 27 and April 29 at both the high school and the elementary school.

“I want to talk about the legacies we leave our children,” she said, “My mother imparted to me a great legacy. From my mother I learned survival, courage, never to give up hope and the value of a human life.”

Olsson’s father also contributed to her personal legacy. Her father was a Hebrew scholar and an educator. Even though he was an educator, Olsson said her father was prejudiced against the public education system and because of that prejudice she didn’t learn how to read and write.

Olsson recounted a story about how she would go into a bank and feign forgetting her eye-glasses, in order that the teller would help do her banking. She kept doing this, until one day she heard her mother’s voice in her head, asking her ‘where is your courage?’

“I knew that day I needed the courage to take the first step to free myself from negativity,” Olsson said, adding that she took that step and told the bank teller she couldn’t read.

“After I took that step and walked through the door you know what I found?” she asked rhetorically. “The sun was shining and I was free of the negativity that was passed down through my early childhood.”

It was the same type of courage that allowed Olsson to survive the horror of being a Jewish-Hungarian.

When Olsson was 19-years-old, in March of 1944 the German army occupied Hungary.

“They just walked in, overnight, because Hungary and Germany were allies,” she said.

It did not take long after the German army arrived before they started to gather up Jewish families and forced them to move into Jewish ghettos.

“There were 19 of us living in two rooms, with one wooden toilet outside and drinking water had to be packed in from two blocks away,” Olsson said. “But that was OK because I had a mom and a dad, brothers and sisters, a grandfather I adored.”

Olsson soon found out their accommodations were only temporary, because on May 15, 1944, the residents in the Jewish slums were told to pack their bags because they were all going to go to work in a German brick factory. Their real destination was the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp in Nazi-occupied Poland.

“They lined us up, five in a row and marched us off to the railway station, seven kilometers away,” she said.

When they arrived at the railway station the residents found what seemed to be an endless line of boxcars.

“We were packed in like sardines in a can.”

In a corner of each of the boxcars, she described how Nazi soldiers placed two pails, one for drinking water and one to use as a toilet.

“One bucket for more than 100 to 110 people,” Olsson said, adding the trip to Auschwitz-Birkenau took many days.

The combination of poor sanitation and cramped conditions meant that some did not survive the trip, with many people succumbing to a combination of dehydration, illness do to sanitary conditions and suffocation due to the lack of air.

Olsson said people believed things would get better once they arrived at their destination.

“We sighed with relief, saying that now we are going to have water and fresh air, but there was neither,” she said.

Instead of fresh air there was a black cloud and foul stench filled the air at the concentration camp.

The stench, she soon found out, was a combination of odors from the gas chambers and the burning bodies at the crematorium.

And as for the fresh water, anyone who asked for water was clubbed, she said.

“I remember turning to my mother and asking, ‘where do we work here’ there is no factory?”

Olsson said she soon found out that the camp was a killing factory.

“At Auschwitz-Birkenau, 2.1 million were murdered, including most of my family,” she said.

Not everyone at the camp was killed. Inmates at the camp were used to stock Germany’s forced labour camps.

Prisoners at Auschwitz were selected for either death or work by the infamous Dr. Josef Mengele, who the prisoners nicknamed The Angel of Death.

All the females were told to strip naked and the young, healthy looking ones 16 and older were instructed to go to the right. Everyone on the left were destined for the gas chambers. Among them was Olsson’s mother.

“I turned my head to the left to see where my mother was, but it was too late,” she said. “I never saw my mother again and how much I wished I could have hugged her one last time and told her that I loved her.”

Despite the atrocities Olsson suffered, including coming within four hours of her own death before her liberation from the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in Germany by British soldiers and Canadian soldiers, she harbours no ill feelings.

“Nothing good comes from hate,” she said, adding that is why she taught her son and her grandchildren not to use the word hate. “Children are not born prejudiced or to hate. It is something they learn and not from school, but in the home.”

That is why Olsson said it is so important parents, grandparents, and other relatives work together to provide children the right example.

“What they learn in preschool (before school, at home) is what they bring to school and into the streets,” she said. “Our responsibility is to send our children to school the way we would like to see them as adults. It is our responsibility, not the teacher.”

This is why Olsson said it is important to stand up to bullying.

“There are no innocent bystanders,” Olsson said, adding that if more countries stood up to Nazi Germany, thousands, if not millions, of lives could have been saved.

“Hitler couldn’t have gotten away with what he did if it hadn’t been for the bystanders of Eastern Europe,” she said, using Czechoslovakia as an example.

In 1938 Germany annexed Sudetenland, a region in Czechoslovakia and by 1939 the country ceased to exist and joined the Third Reich.

“The Allies said let them have it,” Olsson said. “My mom said it is better to say no the first time and that is what we should have done. If we had maybe World War II wouldn’t have happened.”

She also talked about Bulgaria, which was occupied by the Nazi Germany.

“The churches, the bishops, the farmers and lawyers,” Olsson said. “It was a community effort not to be bystanders and not let the trains leave with the Jewish people.”

In the summer of 1943, the gestapo ordered Denmark to send Danish Jews to the death camps. Instead of complying, Olsson said, the Danish people decided stand up to the Nazi bullies and smuggle Danish Jews across a small straight of water in fishing boats to Sweden.

“Why did Bulgaria and Denmark refuse to send those people to the death camps?” Olsson asked. “Because they had compassion.”

After the war, Olsson like many of the survivors of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, was sent to Sweden to recover.

Not only did the people of Sweden welcome the Jewish survivors with open arms and compassion, but it is where she met the person who would eventually become her best friend and husband.

Olsson said it wasn’t religion, education or culture that drew and kept them together.

“It was unconditional acceptance and love for another human being, that is the gift Rudy (her husband) gave to me,” she said. “It is OK to be different. What is not OK is to be indifferent.”

She also said it is a gift she hopes the children she talks to will accept as well.

“It is important to me not only because I want your children to have a future, but because this is the last generation that will be able to put a face to what happened,” Olsson said. “If we forget history, you can rest assured it will repeat itself. Not in my lifetime or in your lifetime but in your children’s lifetime.”