This is Part 1 of a three-part series on home-based education. This week’s story focuses on motivations and challenges faced by families who make the decision to educate their children at home. Next week we’ll look at the expanding role of technology in home-based education. The third part will look at the outcomes experienced by home-schooled students.

It has been a little over a month now that many local children have returned to the classroom, and most are undoubtedly getting back into the swing of things.

School-based education, however, only forms part of the overall picture of education in Westlock and in Alberta as a whole.

There are thousands of children in the province, and perhaps dozens in Westlock, who get their schooling at home — whether with a curriculum aligned with Alberta Education’s or otherwise.

And the reasons for taking part in home schooling are diverse. Parents might have specific religious beliefs they want to instill in their children, which they feel might be compromised in a public school setting. Many students struggle with the social aspects of a public school setting, and parents may choose home schooling to avoid bullying. Still others home school because their children have specific learning needs they feel may not be adequately addressed in a traditional setting.

Westlock residents Craig and Cathy Eklund fall into the first category. For them, the motivation for home schooling can best be summed up with a verse from Proverbs.

“The fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge,” Cathy said. “We just realized that without that foundation, there would be no purpose to it.”

The family, which includes five children ranging in age from one to eight, moved out to Westlock several years ago from Edmonton. They briefly tried a public school approach in preschool with their oldest child, but soon realized they didn’t like the result.

“We had him in a preschool out here, and we weren’t happy with the attitudes and behaviours he learned in preschool,” she said. “All from the other children, not the teacher, so we thought ‘Wow, that’s maybe not the path we want to go on.’”

Specifically their son returned home talking about the movie Dark Knight, which has scenes many parents would consider inappropriate for pre-school children.

“We just wanted our kids to be little boys for as long as they could,” Craig said. “There’s a lot of things they learn, not in school but at school, that we don’t want them to learn about.”

He explained it’s not about sheltering the children from the world, but rather introducing sensitive topics like the sexual and violent aspects of human nature in a way that’s appropriate to the children’s ages and the parents’ belief structure.

Tanya Pollard, another Westlock-area home-school mom, home schools for an entirely different reason. Her six-year-old daughter is high-functioning autistic, meaning she needs some extra supports in her education.

Pollard, who holds a teaching degree herself and taught school for several years in Dawson Creek, B.C., decided that since she has the experience and is able to stay home with her children to teach, she would home-school her children to be able to ensure her daughter gets that support.

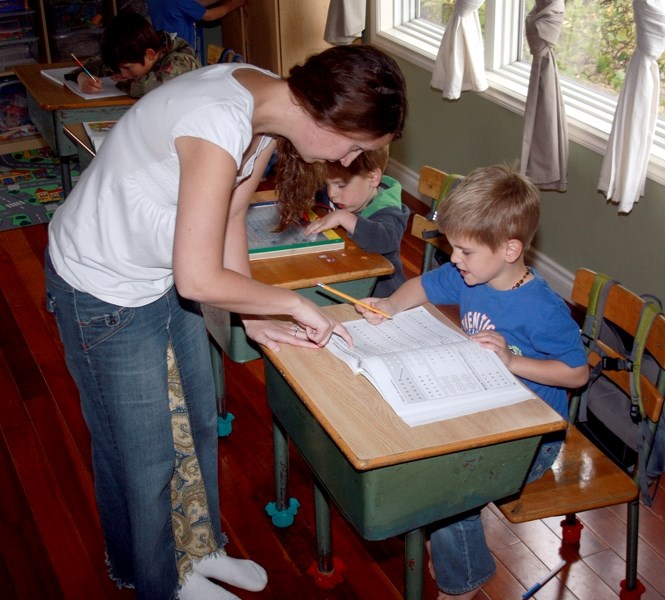

“Our whole home is a school room,” she said. “It’s just a lot more student-focused.”

While these two families represent two distinct motivations for home schooling, there are undoubtedly countless more — in Westlock and across the province.

And while it’s possible for parents to tailor a curriculum to individual learning needs, there is a minimum standard set out by the province.

The School Act states that kids aged six to 16 are required to register to attend some type of school — anything from a traditional public classroom approach to a specialized home-school curriculum.

“Alberta provides a lot of choice,” said department spokesperson Eoin Kenny.

“There is the traditional public or separate schools, private schools, French schools, charter schools and home education programs.”

For students enrolled as home-school students, while they must be registered with a particular school authority, there are many options available. There were 59 different school authorities that registered about 8,000 home-school students in 2011/12.

Parents have the flexibility to fully align their program with the Alberta curriculum, avoid the Alberta curriculum completely, or create a personalized blended program — and there are different school authorities across the province, including some specific to home-schooling, that help parents fulfill those goals.

Generally speaking, all students are expected to meet a set of minimum requirements by the time they graduate — set out either in the curriculum or as learning outcomes for students who do not follow the curriculum.

This set of guidelines includes things like being able to read and write, speak clearly, use math to solve daily problems, understanding the physical world and a host of others.

These guidelines allow for a lot of customization within the curriculum — how the goals are to be achieved is left to the discretion of the parents.

In many cases, however, home-school parents find the ability for the children to learn at their own pace to be one of the biggest advantages — and this includes a lot of time saved in the long run.

“When you look at a typical school day, there’s a lot of wasted time,” Pollard said. “There’s only two or two and a half hours per day of actual instruction.

She noted that given her daughter’s individual challenges, it is best to work in 15-minute bursts interspersed with other activities, something that would not be possible in a traditional setting.

For the Eklunds, the same holds true. They find they are able to get through their particular lessons very quickly, leaving more time to pursue individual interests or learn other life skills.

“Our children do the academics within an hour and a half or two hours, or less, then they have the rest of the day to do other endeavours,” Cathy said. “They learn other things like how to manage a home.”

Both families have found school boards they feel work for their particular needs — Pollard has registered her daughter in the public school system through Pembina Hills school division’s Vista Virtual School, while the Eklunds have chosen a home-school specific board called Learning at Home, based in Okotoks.

While both of these two families will tell you they stand by their choice and believe it’s the right one, neither would suggest there are no disadvantages to this method — although the disadvantages are not the stereotypical ones.

Both Pollard and the Eklunds have heard it all before about how home-school children are weird and anti-social — they just don’t think that assumption is supported by the facts.

The two families are part of a wider support group of home-school parents in Westlock, who meet once a week or more, with kids or without, to discuss the particular issues they face and support each other.

The home-school kids get together as well, and either work together or play together — with a wide age range giving them exposure to a wider variety of social opportunities.

“It’s not like I wake up in the morning and say, ‘Oh my gosh, I forgot to socialize the children,’” Cathy said. “We have a large family to begin with, but our children are very comfortable speaking with adults and older kids.”

“I think home-school kids are socialized better than school kids,” Craig added.

Pollard noted that she always makes an effort to get her daughter involved in social situations outside their home-school classroom, whether it’s with family, friends, or other activity groups in town like the library or the Parent Link Centre. Instead, the challenges associated with this choice seem to be particular to the individual styles of the teachers and learners.

For Pollard, who follows the Alberta Education curriculum, the biggest challenge can be just getting motivated to work. If there’s a topic that’s causing a bit of difficulty, it can be tough to stay motivated — it’s easy to get lazy or put off tasks.

And, like any stay-at-home parent will tell you, when you spend all day with someone you can tend to get a little frustrated with each other.

For the Eklunds, the biggest challenge has come in finding study materials, particularly where commonly accepted ideas come into conflict with the biblical literalism they adhere to.

“We struggle a lot to find appropriate curriculum,” Cathy said. “It’s very difficult to find science books, for example, that don’t believe the theory of evolution is a theory. It’s taught as fact in almost all science books, rather than theory.”

But neither of these families would argue these challenges are anywhere near insurmountable. At the end of the day, they accept these challenges as a small downside to what they see as an overwhelmingly positive experience.

Pollard said for her, one of the best parts about the process is being able to focus on the positive personal characteristics she sees in her daughter and tries to encourage them.

“You have all these wonderful qualities, so let’s grow them,” she said.

For the Eklunds, being able to raise and educate their children in an environment where everything revolves around the teachings of the Bible is priceless.

“We don’t want to keep them away from the world or shelter them from the world,” he said. “We want to teach them the values we think are important.”