Last week, the focus was on healthcare during the Spanish flu that hit in 1918. This week, we took an interest in discussing what changed, if anything. The interesting part of change in the distant past is that its origins are less intuitive to casual observers. It’s curious to hear historians say the Spanish flu had little effect on why or how things changed immediately after the flu when we’re in the midst of a pandemic.

It’s instinct, particularly now in the ‘new normal,’ that dictates to us that things will change because of this pandemic. But did the same thing happen after the Spanish flu?

Emily Kaliel, a PhD student in history at the University of Guelph, has some knowledge of an effort to standardize some portion of healthcare right around the time. But the Spanish flu wasn’t the originator of that conversation.

For her Master’s degree – she worked with Erika Dyck in Saskatoon, – Kaliel focused on the District Nursing Program established by the provincial government in 1919 “that dispatched public health nurse to isolated, rural districts to provide maternal and emergency services to communities otherwise unable to access medical services.”

Near Westlock, nurses were stationed at Jarvie and Fawcett during the interwar period, she said. In the early years of the program, she adds, they were mostly focused on the Peace River area. However, to Kaliel, the program wasn’t exactly a response to the Spanish influenza.

“Provincial rural programming often focused on maternal services and originated from a long history of women advocating for child and maternal welfare services in the province rather than as a particular response to the Spanish flu.

“The First World War and Spanish influenza provided additional support to these conversations because of the massive loss of life – and feminists and child welfare activists argued that mothers and children needed to be healthy and have medical support to rebuild the nation.”

That, of course, couldn’t happen if maternal and infant mortality rates were high, which is what the program was trying to alleviate.

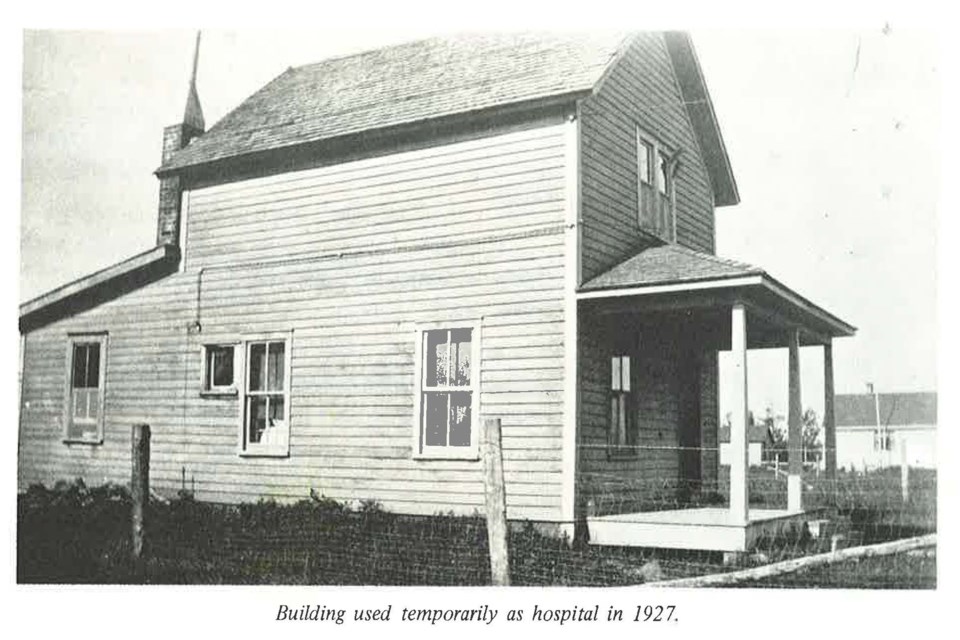

Another example for the Westlock area is, of course, the Immaculata Hospital. Opened in 1927 by the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul of Halifax, this is what a 50th anniversary pamphlet published by the order in 1977 has to say about why they opened it:

“At this time a concerned citizen in the person of Father Eugene Rooney went to Archbishop O’Leary of Edmonton to request that a religious community be asked to open and staff a hospital in Westlock.”

Similar to the hospital in Athabasca at the time, the mayor secured a doctor for the area when the hospital burned down, and the community of nuns contributed to reopening in a different building later in the decade.

Again, it’s at the community level – or, more specifically, at the will of a concerned set of people, including women advocating for widespread healthcare – that change happened immediately.

Specific to the Immaculata, the Spanish flu is absent from any of the reasons provided by those concerned citizens for why healthcare is important.

But looking at the province in general, for historian Erika Dyck the question of whether or not the Spanish flu produced changes in access to healthcare across the Prairies doesn’t have that easy of an answer.

“The influenza wasn’t something that required hospitalization. It was still largely cared for at home and, much like today, under really extreme quarantine measures. It wasn’t so much about putting people in hospitals so much as not letting them out of their homes.

“There were people who would’ve maybe been sent to tuberculosis sanitoriums but those were already considered not a general hospital. They were specifically segregated from larger communities,” she said.

The changes we might expect weren’t there. People didn’t suddenly start doing healthcare differently. Limiting the spread of the flu – i.e. staying health – mirrored the customs of the time: healthcare happens at home.

It’s in a more expansive, long-term capacity that the Spanish flu left marks.

“One of the things that was really apparent in the 1918 epidemic: the role that nurses were playing, or the role that women played. They weren’t paid as nurses, but they were providing a lot of the nursing care. Into the 1920s, if women got married, it didn’t matter if they were trained as nurses, they weren’t allowed to continue working.

“That was not feasible during the pandemic,” said Dyck.

What that means, long-term, is that there’s no direct link between the Spanish influenza and hospitalization. But there is one between the pandemic and how people saw health, namely “the realization that care workers were part of the labour force. We saw some of the biggest labour strikes around the world in the wake of the pandemic.”

Overall, that pandemic seems to have had little to no effect on healthcare provisions or the conversations around specific programming at the time. But it existed as the context in which they happened.

It wasn’t exactly fuel for immediacy, but it was kindling for things to come in the way people thought of healthcare in general.

Returning to specifics, Kaliel added this: “Beyond the District Nursing Program … and three other doctors procured to serve the north from Britain around the same time, I’m not aware of any real coordinated effort to provide rural health services by the province (and would argue that even today, it doesn’t exist in any real form).”

That lack of centralization, which Dyck pointed out last week, wasn’t only prevalent then but it remains active today. Take a look at the front page story for evidence.

There’s one important thing left in this conversation: is centralization necessary? If so, how do we go about making sure that access is equitable? This is how the conversation is happening today, so next week we’ll speak to local decision-makers about their thoughts on healthcare access and who should manage it.

Andreea Resmerita, TownandCountryToday.com

Follow me on Twitter @andreea_res

COVID-19 UPDATE: Follow our COVID-19 special section for the latest local and national news on the coronavirus pandemic, as well as resources, FAQs and more.