ATHABASCA — Did you know bald eagle nests are built so high up, they have no predators, so when researchers endevour to get near their nests, they do not attack ... usually?

Biologist Dr. Elston Dzus works at Alberta Pacific Forest Industries monitoring caribou, but has spent decades helping fund and run the world’s longest running bald eagle monitoring program in his off-time and presented information about the project Oct. 20 as part of Science Outreach – Athabasca's ongoing learning series.

“Dr. (Jon) Gerrard started the project back in 1968 when he was actually an undergraduate,” Dzus said. "They were surveying for eagles, all across northern Saskatchewan or Manitoba, and then in 1970, they decided that they wanted to focus in on one lake and learn more about eagles in one place.”

Dzus and his wife have lived in the Athabasca area for nine years, but have both been active in the study of the birds living around a particular lake in Saskatchewan.

“A road was going to be built sometime in the next five years through this lake called Besnard Lake, which is in northcentral Saskatchewan, by air, it's about 40 kilometers to the west of La Ronge,” he said. “And so, they started (researching) on Besnard Lake in 1968 and the road went in in 1973.”

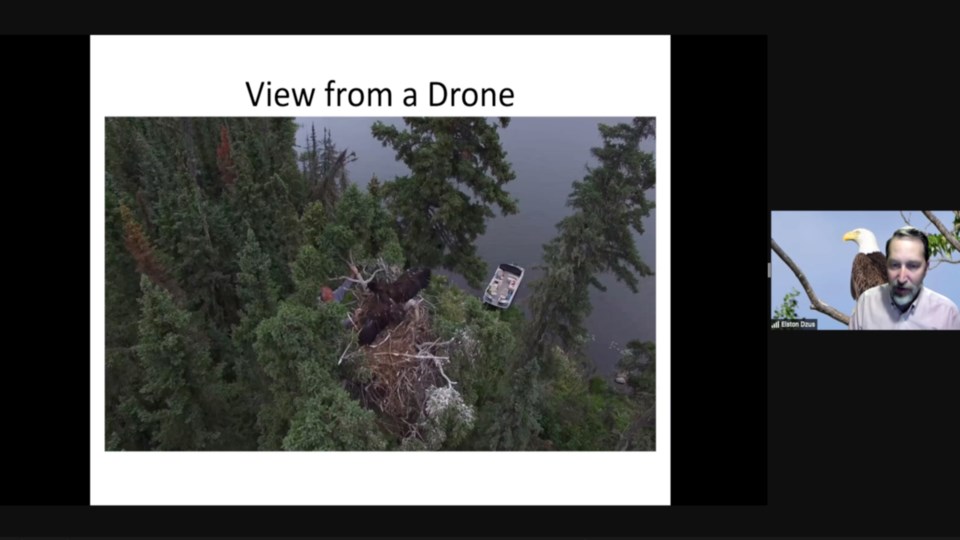

Blinds were built to watch the birds while boats and canoes were used to paddle around the area to determine where their nests were located and occasionally some grant funding would help secure a fixed-wing aircraft to do circle after circle over the area, all to track the raptors.

“It’s an interesting little fact about the distribution and 95 per cent of the nests are within 50 metres of shore, which facilitates searching for them by both air and boat,” Dzus said.

In 1973, waymarkers were introduced by the researchers, coloured bands attached to feathers, as a visual marker to identify where the birds were travelling from.

“What they found was that most of the birds from northern Saskatchewan, were heading south or southeast down to the Missouri area,” he said. “Really basically going only as far south as needed to find large reservoirs and rivers, because they're mainly fish eaters.”

In the early 2000s, it was noted there was a decrease in immature eagles on the lake and it was due to an increase in breeding pairs, with established adults chasing off the younger eagles.

“They don't start breeding on Besnard until they're five or six years old,” Dzus said. “They get their white head when they're four years old, but the territory adults were driving the immatures off Besnard Lake into less productive areas.”

And even with all the interaction with the eagles, there have been a few accidents, either from climbing or being attacked, but he did have a run-in with another bird who had taken over a nest.

“I climbed up to the nest, and it quickly became evident that a great horned owl was nesting there,” he said. “You have to watch the birds with your eyes because typically if you're watching them, they're not going to strike you. I just felt this large thump on my back and so, I knew the adult had struck me. As I'm walking back to the boat I felt like something's not quite right on my back. I reached up and my hand was just covered in blood.”

He survived to tell the tale though, and the full presentation can be found on the Science Outreach – Athabasca website along with upcoming presentations.