WESTLOCK – A pandemic, in the grand scheme of things, is not such a new experience. Those of old have left traces. To uncover how the healthcare system changed over the course of a century and how it absorbed moments of crisis, the Westlock News presents the first of a multi-part series examining documents left behind by contemporaries.

In the history of this province, the Spanish influenza is the immediately remarkable and widely spread health-related event that’s comparable to the current COVID-19 experience. It’s the same for the entire world. It reached Alberta toward the end of the First World War, when the picture of healthcare was entirely different.

That is the focus of this first part.

“When the Spanish influenza pandemic came through in 1918, there was no medicare and there was a real kind of mixture of different kinds of health practices available to people. We know for example that a number of small towns had hospitals. Some of them were run by churches, some of them were missionary hospitals or run by a nurses’ order, but there wasn’t a centralized or standardized approach,” said Dr. Erika Dyck, history professor at the University of Saskatchewan.

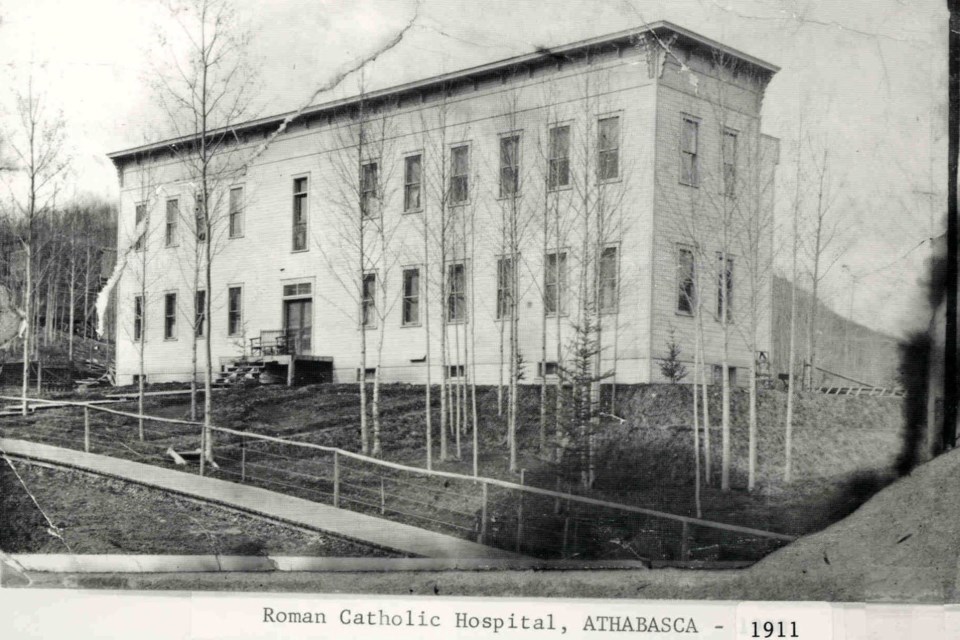

One of those small towns was Athabasca, where the Sacred Hearts Hospital had opened in 1911, built by the Sisters of Providence of St. Vincent de San Paul out of Kingston, Ont.

But there’s really no determining factor for how or why one community might have had hospital and others did not.

Not to mention that, as Dyck says, “people didn’t really go to the hospital unless they were dying.” Healthcare happened in the home.

The only clarity about healthcare at that time is that there was no standardization, certainly no centralization, and that differences can be talked about more at the community level than the provincial one.

Dyck ventured on another speculation too: “The ethnic compositions of the communities seem to also influence how people work together. That might be by pooling money through cooperatives and mutual aid societies, farmer co-ops.

“I believe this is why the Prairies were the place where medicare first started. We saw, in Alberta and Saskatchewan, already around this time, people pooling their funds … to, say, pay a doctor to stay in that community on retainer well before we have anything like medicare.

“We see that in the Prairies, we don’t see it in the Maritimes, even though we could argue that there’s a similar distribution of population. We’ve got a lot of small towns, we’ve got farming communities, people are distributed in a similar pattern but for some reason the combination of the ethnic blend – where people came from – and the desire to pool resources to build homes and communities but then also that spilled into pooling resources to retain nurses, school teachers, lawyers, physicians.

“Already by 1916, some municipalities were paying a doctor a year salary.”

There was a doctor in the Westlock area, remembered as Old Doc Phillips. James G. MacGregor, an area man born at the start of the century, wrote about him in “North-West of Sixteen.” To most folks, it’s clear what that title means.

“From the most remote shack 35 miles away in Neerlandia they came to him, galloping all through the night. From the edge of the great muskegs up Naples way they rushed to him. From Mellowdale, Paddle River, Lunnford, and Belvedere they sought his help for a loved one labouring long in childbirth or stricken with fever. Along the trails to Dunstable, Arvilla, and Picardville, Old Doc and his driving team fought their way for years through mud or storm to the bedside of a sick mother or a wasting child,” wrote MacGregor.

In Athabasca, the hospital had burned down in 1916, so the mayor at the time, George Mills, acquired a physician for the area: Dr. George William Meyer.

As for Doc Phillips, MacGregor expresses in the memoir that it was curious to him and many others that the doctor from Michigan would’ve left home and set up a new one on “the only quarter in the whole community considered useless.”

His family and the doctor were neighbours. That only bad quarter, MacGregor wrote, was on the south-east of 17, diagonally from his family’s farm.

At the time of the pandemic, Westlock was a village of about 220 people, and Athabasca a town of 400. Barrhead wasn’t incorporated until later. The makeup of the municipal districts around them was much, much different than what a map displays today, but most around these parts are listed at anywhere between 300 and 500 resident farmers.

There are few records in personal histories of what living with the Spanish flu must have been like. MacGregor wrote about masks, for example, but he was only 13 at the time.

Florence Roberts, an Athabasca native whose memories of that time survived, had this to say: “We had bad news from home. It told of the terrible influenza pandemic which had swept the community … It was not until we returned [to Athabasca] in April that we realized the full impact of that dreadful time.

“Thankfully, we found all the members of our family, though not escaping disease, had survived. There was sad news though, of one and another friends and neighbours who had died and it seemed that some of the strongest and most vigorous were most prone to succumb.

“There were stories of heroism and endurance and the inherent goodness of man, which always becomes apparent in times of adversity.”

Although Roberts was more inclined to have observed and noted small changes in how people behaved at that time (that “goodness of man”) both she and MacGregor particularly remember the role of the doctors.

“No one served more tirelessly or with less concern for personal risk than the family doctor. He was Dr. George Meyer, the only doctor in Athabasca, and it was he who battled cold and biting wind and weariness in the long drives between homesteads in an open, horse-drawn cutter,” wrote Roberts.

For MacGregor, it was decisively notable that once the Spanish flu had gone, the doctor passed away.

“Finally there came the Spanish flu of 1918. Far away in Swallowhurst or Sunniebend, through blizzard and snowdrift, Old Doc rode, dozing between calls, hastening to fight it.”

The death toll rose to 4,000 – about 38,000 people were infected – between 1918 and 1920, when Alberta’s population was around 500,000. Next week, we’ll look at what, if anything, came out of this pandemic.

Andreea Resmerita, TownandCountryToday.com

Follow me on Twitter @andreea_res

COVID-19 UPDATE: Follow our COVID-19 special section for the latest local and national news on the coronavirus pandemic, as well as resources, FAQs and more.